Granting of land tenure in Medellin, Colombia’s informal settlements: Is legalization the best alternative in a landscape of violence?

Abstract

Colombia’s long history of internal violence has been characterized by the displacement of populations caused by the armed actors of the conflict. Colombia has one of the world's largest populations of internally displaced persons (IDPs) in the world, estimated to be as many as 4.3 million people (Yacoub 2009). These populations, the majority of which are rural, seek safe(r) locations in large urban centers like the cities of Bogota, Medellin and Cali (Lozano-Gracia et. al. 2010), where they become part of the growing population of slum dwellers. This situation of displaced people’s in cities has been complicated in Colombia by the fact that the national conflict has escalated and extended into these same urban areas where displaced people have built housing (informal settlements). Today a subgroup of this displaced population that has arrived to the city, had to migrate again from one area of the city to others out of fear of leaving their homes or selling them under pressure of these urban armed illegal actors. All of this has happened in the context of an ongoing land granting process by the state (Rojas 2010) that follows the logic that granting of land titles adds economic benefits both to the state and to the dwellers. This project has been developed at a national level and in Medellin for the last 15 years. This paper seeks to understand the challenges of policies that grant titles in informal settlements as a tool to deal with the growing problem of informality in Medellin, Colombia against the backdrop of a landscape of urban violence. It also suggests how communal grant title could be a tool that places these communities in a less dangerous position.

Background

The city of Medellin, Colombia, like many cities in Latin America, has seen a demographic explosion over the past six decades. In Colombia, this accelerated growth has its roots in the forced migrations that started with the civil unrest of the early 1950’s know as “La Violencia”. This civil unrest has consequences until the present. This produced large migrations from the rural areas to the “safer” urban centers. These rural populations fled to the cities, often without any belongings or economical assets because they had to leave suddenly with no time to pack their things. They have encountered a city where the political system lacks the necessary legal and social legitimacy to control the national and local territory and an economical (industrial) sector unable to cope with the effects of globalization (Betancur 2004), thus diminishing job opportunities for those just arriving.

Those families and individuals just arriving from the countryside only find housing opportunities in the informal housing sector through a process of “invasions” (land grabbing). As a result of this process “nearly 2/3 of the population [of Medellin] currently lives in barrios that do not comply with the minimum standards and that lack the proper facilities” (Betancur 2007).

As a result of these national and local issues since the mid 1980s, Medellín has been an extraordinarily violent city, even within the context of Colombia. In the last wave of violence in Colombia between 1989 and 1994, (Betancur 2007), Medellín experienced 25 percent of all public order problems in the entire country.[1] In a country with a century-long history of violence and an internal civil war, Medellín has been the territory where those consequences were among the most visible.

The areas of informal settlements in the city are where the complexities of the national conflict, with its multiplicity of illegal armed actors (drug lords, guerrilla, Right Wing Paramilitary groups and organized criminal gangs), intersected. Historically each one of these illegal armed actors of the national conflict had positioned themselves in the major cities like Medellin and fought for control of the informal territories that are outside of control of the formal state.

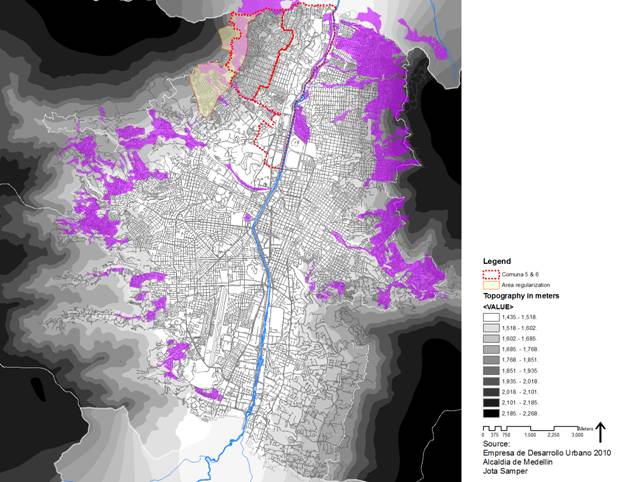

Over the last two decades, the city of Medellin has implemented a series of projects that tries to deal with the problem of informality. The first project, implemented in the early 1990s, was the PRIMED (Integrated Slum Upgrading Program of Medellin or Programa Integral de Mejoramiento de Barrios Subnormales en Medellín). The second project, implemented in Medellin in 2004 to the present, was the Integral Urban Project (IUP) (Programa Urbano Integral). Both of those consecutive strategies focused on granting of land titles to informal settlers along with other polices and projects that intended to incorporate these “substandard” areas to the rest of the city. See Figure 1 for a map of all informal settlements’ of the city of Medellin and the ones that are considered for regularization.

Figure 1 Medellin's informal settlements’: in purple are all informal settlements, in yellow there is a new area declared for regularization.

These projects that include the granting of titles in informal settlements of Medellin had been done in the midst of two national policies of pacification: (1) an increased increment in the use of military force toward illegal groups, funded by the US Plan Colombia that targeted left wing guerrillas and (2) the controversial (some authors will consider failed) peace process with the right wing Paramilitary group AUC (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia). Both policies had occurred in rural and urban areas. The city of Medellin has been one of the cities in Colombia most impacted both by the actions of these groups and by the consequences of the failed peace process. Medellin, by 2007, had 13% of the total national demobilized personnel.

As a result of the complex and failed peace process with illegal armed actors in Medellin, the ex-militants of the paramilitary groups that once were part of the peace process had regrouped into a multiplicity of small gangs “Combos, Bandas and Oficinas” (Avendaño 2009). These groups[2] had a larger presence in informal settlements. See Figure 2. This is a map that graphically shows how the previous paramilitary organization has fragmented into a multiplicity of illegal armed actors distributed over the territory of the Comunas 5 and 6.

Figure 2 Comuna 5 and 6 Distribution of Illegal armed groups 2009: In red are the territories controlled by each one of the gangs (Combos or Bandas) that operated in 2009 in the Comunas 5 and 6.

Asset appropriation through fear

The military actions of the armed groups in Colombia and most commonly of the right wing paramilitary groups have coincided with attempts to acquire land, not only for the control of the security but to use land as an asset. Literature on the subject of illegal armed actors in Colombia displacing population as a tool of land grabbing concentrates on the effects of this phenomena in rural areas (Romero 2003 and Comisión Intereclesial de Justicia y Paz 2007), where the issue is clearer because farmers usually had some form of legal proof of tenure. By contrast, in informal settlements in urban areas the tenure of entire communities is a contested issue and the thus the phenomena is less documented.

In interviews conducted in January of 2010 in informal communities in Medellin (Samper 2010) revealed that some of the urban warfare tactics employed by paramilitary groups in Medellin include housing appropriation for the use of the asset as strategic location and the forced displacement and murder of individuals who threatened the illegal organization standing.

In Medellin, with a population of 2.636.101,[3] the total number of officially displaced people by the armed conflict by 2010 is 178,486,[4] 6% of the total city population. From that group, 13.541 are interurban displaceded,[5] (this number represents 20% of the national total of interurban populations).[6] That final number is the official number of individuals being displaced by the tactics of these groups. The areas of operation of illegal armed groups in Medellin are usually informal settlements and these are the areas that now are selected by the local government as areas to grant legal tenure to their inhabitants.

Medellin, Colombia Legalization of Title

The Medellin regularization project dates back from 1994 and up to today many communities have benefited from the developments of the project. The project has gained recognition by some development agencies like the UN –Habitat Best Practices database as good practice. There is a large body of literature on the intrinsic benefits of granting tenure and the way that that the title regularization project creates economical benefits for both the household and for the state:

Results indicate that the value of a dwelling with a legal title is, on average, 37 percent above that of a house without one (approximately US$700 per dwelling), amply justifying the financial cost of the titling process (approximately US$80). Additionally, there are financial benefits for the state coming from increased land tax yield (US$11 per year per property) and the value added tax on notary services (US$4 per house sold in the market)”. (Rojas 2010)

Figure 3 Project already approved PUI NorOccidental Source Alcaldia de Medellin, Empresa de Desarrolllo Urbano. In light yellow is the area selected to grant titles.

Today the PUI Proyecto Urbano Integrado Noroccidental (urban integrated project nor-western) that focused its efforts in the Comunas 5,6 and 7 involve a total of 9,242 homes as part of the legalization regularization and title program since 2004. From that, a total of 8,000 homes alone will be regularized during the 2008-2011 mayoral period.[7] The informal settlements selected for development are described in the “Proyectos Plan de Desarrollo. 2008-2011. -Proyecto Plan De. Regularización. Convenio 480002183 de 2007”

Question

Today these two situations (1) large presence of diverse number of illegal armed actors and (2) granting of titles as part of the plan of regularization intersect the same territory. This intersection and the way in which the regularization process has been conducted may be leading to unexpected and possibly undesirable outcomes given the influence of illegal armed actors. Specifically, in terms of how these illegal armed actors modify occupancy of those housing units to be regularized.

In 2002 after a military operation (Operacion Orion) in Medellin that sought to eliminate a stronghold of left wing urban guerrilla in the Comuna 13, (dhcolombia, 2007), a contingent of the right-wing paramilitary group (Cacique Nutibara) moved to the area. As part of their military strategy they targeted individuals (killed, expelled or intimidated) who allegedly had links with the previous regime. As part of a series of interviews that I conducted in January 2010 in the Comuna 13, a member of the community narrated that along with this process of displacement of population, this organization also evicted families housed in strategically located units. Today the illegal armed groups that operate in the Comunas 5 and 6 are the factions of the “demobilized” right wing paramilitary groups that continue the same extortion and drug-trafficking practices. So it is expected that those same tactics applied for this territory.

Figure 4 Comuna 5 and 6 with IUP projects and areas of regularization and territories’ of gangs.

I suggest that these kinds of experiences might be the kind of situations happening now.

· If the process of legalization to individuals is increasing their asset value, this operation could increase their susceptibility to be the targets of extortion. Illegal armed groups would seek to capture that gain either by direct extortion or by appropriation of the housing units as in the case of Comuna 13.

· If we assume, as does some of the literature in legalization, that granting titles is an incentive to improve the housing units, this again opens a venue of extortion of those individuals who invest in improving their units. In July 2010, the human right’s board of Comuna 6 in an open letter to the mayor of Medellin exposed that contractors building the new city owned daycare center were being extortion and had to pay extortion to the illegal armed group. If projects by the state cannot avoid being extorted, what about single home owners?

This intersection opens a series of important questions:

a. In this context, what are the implications of a process of granting of titles in informal settlements where scare tactics have been used to expel populations to other areas?

· Is the granting of a single title a good strategy under this context?

· Does single land title permit illegal armed actors to more easily capture the aggregated value that properties acquired after grating of legal title?

· Does single granting of title put communities in more danger because it increase the perceived asset gain? In other words, are individuals who acquire titles more susceptible to extortion than before?

b. What kind of title structures can be more effective in areas where scare tactics are used to remove population and where illegal armed actors maintain control and contest the legitimacy of the state?

Alternatives

I propose to explore communal property ownership as a more effective system than the granting of titles to individuals in informal settlements. I suggest here that communal property titles will make individuals less susceptible to land expropriation by illegal armed actors—by coping with the aggregated issues of legalization in the contexts of violence in Medellin, Colombia.

I assess the possibility of this tool of communal property ownership through examining three international cases that were communal agreements and ways they added leverage to these communities or diminished perceived acquired land value.

Shared equity homeownership, in the United State communal or shared ownership systems had been created to provide affordable housing to several generations by limiting the ability of an individual to capture all the equity on their affordable properties (Davis 2006). The owners in shared equity homeownership “[a]re not allowed to walk away, however, with all of the value embedded in their property.” Here equity is controlled by the communal agreement, which in the Medellin case would make individuals less susceptible to extortion by their perceived gain.

Mumbai India communal land granting “Contrary to most tenure legalization programs, Mumbai’s Slum Upgrading Program (SUP) was not based on individual private property rights. Instead, tenure was legalized on the basis of cooperatives. Mumbai’s policy makers decided to use the cooperative structure because it was difficult to define individual land-holdings in the city’s haphazardly laid-out sums” (Mukhija 2002). Another important result of this process is that a “key outcome of the cooperative form was that it created an imperative for the cooperative’s members to act collectively” (Mukhija 2002). Here the communal property rights are seen as a way to streamline the regularization process as well as to strengthen communal governance.

Communal property rights in the Changing District in Beijing the conversion of villages’ collective assets into a new form of shareholding cooperative along with the election of a new board of directors. This had a profound impact in increasing the leverage that the community had against developing forces from the state and private developing companies. This example “shows how grassroots officials have become the major agents in these bottom-up social and political reforms in China” (Po 2011). This example shows how changes in communal ownership and governance can bring benefits of increased leverage against powerful external actors to communities on risk like the ones in Medellin.

Possible scenarios

In the Comunas 5 and 6 there is today a growing system of governance. Today both comunas administer their own participatory budget (PB). In Medellin the total budget for the PB represents 10% of the total investment budget of the city. These comunas also develop their own planning strategies even in the midst of violence and conflict and had the precedence of Human Rights and NGO’s groups. All this signifies a good initial communal base to implement a project like this.

Based on my understanding of both the cases of communal property right agreements and the situation of regularization in Medellin, the following pro and con scenarios emerge:

Pros

· Communal property rights can increase leverage of communities’ traditional marginalized in Colombia. It could add social capital to already established communal institutions and would, like in other places, serve as a force to increase the level of action of those existing organizations.

· The Comunas in Medellin already had initial stages of self governance systems in place (participative budget and communal planning practices) Esperanza Gomez (2007). Even if these systems are still largely supervised and easy to control from the central government (Gomez 2007), the opportunity of using communal land tenure as a tool to strengthen those communal institutions can further legitimize and support the efforts of the community.

· It would be easier to implement a regularization project if cooperative or communal systems were implemented instead of using single land titles.

· Communal land titles can be extended to areas of protection close to housing to be regularized, making communities co-responsible for the preservation of these areas. Using single titling, in a way, encourages individuals to appropriate these protection areas. Making the community responsible for it would help to avoid that newly arrived individuals place their homes in areas of risk.

· The communal property rights make individuals less susceptible to lose the total value of their unit if they are force by illegal armed groups to leave the neighborhood.

Cons

· Individuals participating in a communal land agreement will not necessarily benefit from the same asset appreciation as those that participate in single grant tenure.

· Given that state organization legitimacy is challenged by the presence of diverse number of illegal armed actors for decades in these neighborhoods, it is clear that even strong communities will have small repressive power to control those illegal organizations and thus these type of measures also need to be assisted by other measures that reduce the risk that individuals had in these areas.

· Comunal property rights required a high level of communal organization. Today there is no certainty that the Comunas 5 and 6 possess that level of communal organization. Those existing organizations depend at large on state institutions or NGOs foreign to the comunas, and this dependency on foreign help can limit the autonomy of any communal organization around property rights.

· Irregularities in the way the communal organization that controls the land title can jeopardize livelihoods of the entire community.

Bibliography

Alonso, Manuel y Valencia, Germán. (2008, julio-diciembre). Balance del proceso de Desmovilización, Desarme y Reinserción (DDR) de los bloques Cacique Nutibara y Héroes de Granada en la ciudad de Medellín. Estudios Políticos, 33, Instituto de Estudios Políticos, Universidad de Antioquia, 11-34.

Alcaldia de Medellin. 2010 Secretaría de Bienestar Social Gerencia Para la Coordinación y Atención a la Población Desplazada, Unidad De Análisis Y Evaluación De Política Pública “Análisis del contexto y la dinámica del desplazamiento forzado intraurbano en la ciudad de Medellín” july.

Alzate Zuluaga, Mary Luz. 2010 The Hegemonic Discourse about Collective Actions of Civil Resistance: Cases Communes 8, 9 and 13 of Medellín. Estud. polit., Medellín. [online]. Jan./June, no.36 [cited 18 October 2010], p.67-93. Available from World Wide Web: <http://www.scielo.unal.edu.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0121-51672010000100004&lng=en&nrm=iso>. ISSN 0121-5167.

Avendaño, Mary Luz. 2009. Las bandas de Medellín | ELESPECTADOR.COM. April 8. http://www.elespectador.com/articulo135143-bandas-medellin.

Betancur, John J. 2007 "Approaches to the Regularization of Informal Settlements: the Case of PRIMED in Medellin, Colombia." Global Urban Development Magazine, November. http://www.globalurban.org/GUDMag07Vol3Iss1/Betancur%20PDF.pdf (accessed February 2, 2010).

Anon. 2009. Colombia's displaced 'rises 25%'. BBC, April 23, sec. Americas. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/8014085.stm.

"COLOMBIA - Paramilitary in redistributed land scam". 2006. Latin American Weekly Report. (15): 6.

Davis, John Emmeus. 2006. Shared equity homeownership: the changing landscape of resale-restricted, owner-occupied housing. Montclair, N.J.: National Housing Institute.

Gómez Hernández, Esperanza. 2007. El presupuesto participativo entre democracia, pobreza y desarrollo. 15: 0121-3261.

Ramirez, Ivan Dairo. Medellín: Los niños invisibles del conflicto social y armado. Rio de Janeiro: Viva Rio, 2006 (www.coav.org.br)

"Los señores de las tierras." SEMANA, May 28, 2004. http://www.verdadabierta.com/paraeconomia/206-los-senores-de-las-tierras- (accessed October 17, 2010).

Lozano-Gracia, Nancy, Gianfranco Piras, Ana Ibáñez, and Geoffrey J. D. Hewings. 2010. "The Journey to Safety: Conflict-Driven Migration Flows in Colombia". International Regional Science Review. 33 (2): 157-180.

Mukhija, Vinit. "An analytical framework for urban upgrading: property rights, property values and physical attributes." Habitat International 26 (2002): 553-570(18).

Po, Lan-chih. "Property Rights Reforms and Changing Grassroots Governance in Chinaʼs Urban-Rural Peripheries: The Case of Changping District in Beijing." Urban Studies forthcoming (2011).

Rojas, Eduardo. 2010. Building cities neighborhood upgrading and urban quality of life. [Washington, D.C.]: Inter-American Development Bank. http://idbdocs.iadb.org/wsdocs/getdocument.aspx?docnum=35132311.

Rozema, Ralph. 2007 "Urban DDR-processes: paramilitaries and criminal networks in Medellín, Colombia". 2008. Journal of Latin American Studies. 40 (3): 423-452.

Soto, Hernando de. 1989. The other path: the invisible revolution in the Third World. New York: Harper & Row.

Yacoub, Natasha. 2009. Number of internally displaced people remains stable at 26 million (May 4). http://www.reliefweb.int/rw/rwb.nsf/db900SID/EGUA-7RQN5C?OpenDocument.

Comisión Intereclesial de Justicia y Paz. Blanquicet (Urabá): Apropiación paramilitar de TIERRA, Dilación Institucional : Indymedia Colombia. http://colombia.indymedia.org/news/2007/05/64872.php.

Romero, Mauricio. 2003. Paramilitares y autodefensas, 1982-2003. Bogotá: Temas de Hoy ;Instituto de Estudios Políticos y Relaciones Internacionales Universidad Nacional de Colombia ;Editorial Planeta Colombiana.

dhcolombia. 2007. Cinco años de la Operación Orión: No más mentiras -. October 14. http://www.dhcolombia.info/spip.php?article432.

[1] “With 7% of the national population, the city reported 25% of public order problems in the country in 2001.”

[2] Some authors refer to these new organizations as “neo-paramilitary groups” because of their possible alliance with political ideologies or the dismantled paramilitary groups. I opt to use the self denomination use by these groups because it is unclear that all groups had or maintained linkages with the previous organizations. Also because, even when they self proclaimed, under the peace process, to be part of the paramilitary groups, the actual link was called into question by human rights groups during the questioning about the improprieties of the peace process.

[3] Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística DANE, CENSO GENERAL 2005 2.636.101 in the city of Medellin and a total of 3.729.970 in the Metropolitan area.

[4] Total official displaced population is taken from public records of “Accion Social” Agencia Presidencial para la Accion Social y la Cooperacion International., SIPOD, accumulated by May 31, 2010.

[5] Interurban displacement is the forced displacement of population (individuals, families or communities) by illegal armed groups inside the boundaries of the city, all against a landscape of generalized violence armed conflict and violations of human rights.

[6] Alcaldia de Medellin, Secretaría de Bienestar Social Gerencia Para la Coordinación y Atención a la Población Desplazada, Unidad De Análisis Y Evaluación De Política Pública “Análisis del contexto y la dinámica del desplazamiento forzado intraurbano en la ciudad de Medellín” July 2010.

[7] “8.000 hogares accederán al mejoramiento de las condiciones habitacionales básicas (mejoramiento del entorno, legalización, titulación, regularización, acompañamiento social). Para el período 2004-2011 se habrá logrado que 9.242 hogares mejoren sus condiciones habitacionales” Medellin Plan de Desarrollo 2008-2011, Alcaldia de Medellin

Llegué a http://cuantonecesitoparaelfinal.com.co/ cuando estaba planificando mi estrategia para los exámenes finales y me sorprendió lo útil que resulta para anticipar el puntaje necesario.

ReplyDelete