Testing the Informal Development Stages Framework Globally: Exploring Self-Build Densification and Growth in Informal Settlements

Abstract

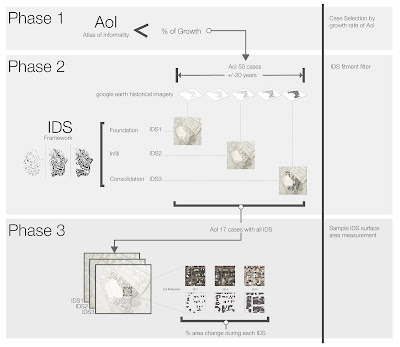

This article challenges the narrow definition of informal settlements as solely lacking a formal framework, which overlooks the dynamic city-making and urban design processes within these areas. Communities’ self-building processes and areas’ constant growth are indeed informal settlements’ most salient morphological features. The study builds upon the informal development stages (IDS) framework and explores how it applies globally. The research follows a sample of fifty informal settlements with a high change coefficient from the Atlas of Informality (AoI) across five world regions to explore how change and urban densification across IDS can be mapped in such areas using human visual interpretation of Earth observation (EO). The research finds evidence of IDS framework fitment across regions, with critical morphological differences. Additionally, the study finds that settlements can pass through all IDS phases faster than anticipated. The study identifies IDS as a guiding principle for urban design, presenting opportunities for policy and action. The study suggests that integrating IDS with predictive morphological tools can create valuable data to refine identification models further. Finally, the article concludes that an IDS approach can anticipate development and integrate into an urban design evolutionary process that adapts to the deprived areas’ current and future needs.

Program in Environmental Design, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO 80309, USA

*

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

Urban Sci. 2023, 7(2), 50; https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci7020050

Conclusions

A recurrent framework of defining informal settlements (IS) has a singular goal of reaching formality. As such, development agencies define “slums” as areas that “lack” the expected features of a formal city (e.g., durable housing, sufficient living area, access to improved water, access to improved sanitation facilities, and secure tenure). Focusing on the lack of a (formal) framework results in overlooking the processes that make these urban forms and communities who live there different from the traditional western perspectives of city-making and urban design. Communities’ self-building processes and the areas’ constant growth are indeed informal settlements’ most salient morphological features. These features then permit the identification, mapping, and creation of geometrical models that ultimately help scholars predict informal settlements’ growth. Part of the challenge of accurately defining informal settlements is limiting our understanding to fixed characteristics regarding an urban form in constant flux. This research builds upon the informal development stages (IDS) framework to measure rates of change in IS and explores how such structures apply globally. The informal development stages (IDS) framework is a categorization matrix that has been developed to classify the age and level of densification in informal settlements [13]. The IDS created three unique thresholds of densification that determine patterns of urban form. The first one, foundation, represents the lowest level of density, which is followed by infill, an increase in population and urban density and a diminishing quantity of open space due to the growth of existing units. Finally, during consolidation, the units’ quality improves, and most growth happens in the third dimension (upward).

The research follows a sample of fifty informal settlements with a high change coefficient from the Atlas of Informality (AoI) across five world regions to explore how change and densification across IDS can be mapped in such areas. The research found evidence of change and densification across regions. From the 50 settlements sample, a total of 94% demonstrated densification changes that fit the IDS model. Furthermore, the timeframe of densification does not appear to have had a significant impact on the outcomes. IDS evidence can be found in newer settlements, some only 12 years old. After reviewing samples of settlements using IDS, we observed clear densification patterns between different stages and significant changes in area coverage rates during transitions. Specifically, the area coverage increased by an average of 225.6% between IDS1 and IDS2 and by 73.87% between IDS2 and IDS3. This difference is significant for classification and the creation of a policy tailored to the rates of change at each IDS.

Additionally, the research found that large settlements can exhibit all IDS simultaneously, meaning that as older areas densify, new expanding areas are created. The sample demonstrates a significant reason to believe that the IDS framework has evidence across regions. However, cultural and architectural typologies result in differences across regions. Furthermore, time changes happen at different speeds, probably reflecting each case’s political and economic local context that later reflects on the densification process. This research selected cases from the AoI; this introduced a potential identification bias toward new settlements with high rates of change. Additionally, the AoI standardized samples from a diverse methodological identification process and represented different contexts. Future research using further multiple methods could examine these changes on the ground more thoroughly.

In conclusion, this research highlights the importance of considering the self-building processes and constant growth of informal settlements in our understanding of urban forms. The IDS framework provides a comprehensive and dynamic approach to defining and understanding informal settlements, which is crucial in accurately predicting their growth and development. This research also demonstrates the global applicability of the IDS framework and highlights the need for further research to understand the unique morphological features of informal settlements worldwide. This research engages with the literature of understanding the morphology of informal settlements. It builds on a theoretical framework to classify them based on their unique characteristic of ongoing urban densification.

The possibility of classifying informal settlements based on their progressive densification, as expected in the IDS framework, presents opportunities for policy and action in informal settlements. For example, the predictive nature of model changes can help city governments to develop projects and funding in anticipation of future changes. Furthermore, classifying informal settlement areas by IDS can help city governments to include in city planning efforts a budget tailored to each place, concerning their needs more effectively.

An inherent danger exists in visibilizing poor marginal communities in informal settlements. Making these areas and their future change evident can also incentivize the dangerous actions perpetuated by slum eradication practices. Therefore, we must be vigilant about how such methods can serve as an excuse for further imposing harm and violence on these population groups. However, we need to also understand that the invisibilization of informal settlements does not automatically mean the protection of such communities and that their lack of recognition is also a strategy long employed to facilitate the use of violent and harmful practices.

The next step is to apply such new knowledge in the interventions in informal settlements. Improving the current urban upgrading practices means moving beyond palliative design responses to what informal areas lack. Instead, an IDS approach looks at growth and change as guiding principles of urban design by looking at not-developed areas as part of the intervention strategy, anticipating future development and integrating into the urban design not as a finite image of the neighborhood but as an evolutionary process that adapts to these settlements’ current and future needs. Finally, adopting an IDS urban design approach would require a radical change in how we approach design in these areas in terms of the regulatory framework and funding strategies, all of which are nonexistent today, as well as the creativity of multiple actors in developing new urban design paradigms of intervention in the planet’s most common form of development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S.; methodology, J.S.; software, W.L.; validation, J.S. and W.L.; formal analysis, W.L.; investigation, J.S. and W.L.; resources, J.S.; data curation, J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.S.; writing—review and editing, J.S.; visualization, W.L.; supervision, J.S.; project administration, J.S.; funding acquisition, J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

AoI settlement information can be accessed at www.atlasofinformality.com (accessed on 15 April 2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Desa, U.N. World Urbanization Prospects, The 2018 Revision; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2018; p. 126. [Google Scholar]

- Samper, J.; Shelby, J.A.; Behary, D. The paradox of informal settlements revealed in an ATLAS of informality: Findings from mapping growth in the most common yet unmapped forms of urbanization. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2019; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019; p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M. Planet of slums; Verso: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 1-84467-022-8. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, S. How slums can save the planet. Prospect 2010, 167, 39–41. [Google Scholar]

- Mayne, A. Slums: The History of a Global Injustice; Reaktion Books: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 1-78023-887-8. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, A. The return of the slum: Does language matter? Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2007, 31, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abascal, A.; Rothwell, N.; Shonowo, A.; Thomson, D.R.; Elias, P.; Elsey, H.; Yeboah, G.; Kuffer, M. “Domains of deprivation framework” for mapping slums, informal settlements, and other deprived areas in LMICs to improve urban planning and policy: A scoping review. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2022, 93, 101770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuffer, M.; Pfeffer, K.; Sliuzas, R. Slums from space—15 years of slum mapping using remote sensing. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Crooks, A.; Koizumi, N. Simulating Spatio-Temporal Dyanmics of Slum Formation in Ahmedabad, India. In Proceedings of the 6th Urban Research and Knowledge Symposium - Rethinking Cities: Framing the Future, LSE Cities. Barcelona, Spain, 8–10 October 2012; Volume 2012, p. 336387-1369969101352. [Google Scholar]

- Samper, J. Forecast Anticipate and Condition: Informal Development Strategies in Mumbai. In Landscape + Urbanism around the Bay of Mumbai; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010; ISBN 81-901974-8-7. [Google Scholar]

- Samper, J. An urban design framework of informal development stages: Exploring self-build and growth in informal settlements. In The Routledge Handbook of Urban Design Research Methods; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2023; p. 528. ISBN 978-0-367-76805-8. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, J.; Sobreira, F. City of slums: Self-organisation across scales. UCL Work. Pap. Ser. 2002, 55, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, E. Regularization of Informal Settlements in Latin America; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; ISBN 1-55844-202-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, K.T.; Vaa, M. Reconsidering Informality: Perspectives from Urban Africa; Nordic Africa Institute: Uppsala, Sweden, 2004; ISBN 91-7106-518-0. [Google Scholar]

- Huchzermeyer, M. Unlawful Occupation: Informal Settlements and Urban Policy in South Africa and Brazil; Africa World Press: Trenton, NJ, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-1-59221-211-8. [Google Scholar]

- Leeds, A. The Significant Variables Determining the Character of Squatter Settlements; University of Texas: Austin, TX, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrotra, R. Kinetic city, Issues for urban design in South Asia. In Reclaiming (the Urbanism of) Mumbai. Explorations in/of Urbanism; Sun Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 142–152. [Google Scholar]

- Kamalipour, H.; Dovey, K. Mapping the visibility of informal settlements. Habitat Int. 2019, 85, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, M. Verb Crisis; Actar: Barcelona, Spain; New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-84-96540-97-2. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.Q. Housing for All: The Challenges of Affordability, Accessibility and Sustainability: The Experiences and Instruments from the Developing and Developed Worlds; Human settlements finance and policy series; United Nations Human Settlements Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2008; ISBN 978-92-1-131992-7. [Google Scholar]

- Boanada-Fuchs, A.; Boanada Fuchs, V. Towards a taxonomic understanding of informality. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2018, 40, 397–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huchzermeyer, M.; Karam, A. Informal Settlements: A Perpetual Challenge? UCT Press: Cape Town, South Africa, 2006; ISBN 1-919713-94-8. [Google Scholar]

- Arfvidsson, H.; Simon, D.; Oloko, M.; Moodley, N. Engaging with and measuring informality in the proposed Urban Sustainable Development Goal. Afr. Geogr. Rev. 2017, 36, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliuzas, R.; Mboup, G.; de Sherbinin, A. Report of the Expert Group Meeting on Slum Identification and Mapping; CIESIN: Palisades, NY, USA; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya; ITC: Enschede, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Taubenbock, H.; Kraff, N.J. The physical face of slums: A structural comparison of slums in Mumbai, India, based on remotely sensed data. J. Hous. Built Environ. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2014, 29, 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuffer, M.; Orina, F.; Sliuzas, R.; Taubenböck, H. Spatial patterns of slums: Comparing African and Asian cities. In Proceedings of the 2017 Joint Urban Remote Sensing Event (JURSE) IEEE, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 6–8 March 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Purwanto, E.; Sugiri, A.; Novian, R. Determined Slum Upgrading: A Challenge to Participatory Planning in Nanga Bulik, Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, P. Detecting Informal Settlements from IKONOS Image Data Using Methods of Object Oriented Image Analysis-an Example from Cape Town (South Africa). In Remote Sensing of Urban Are-as/Fernerkundung in Urbanen Räumen; Jürgens, C., Ed.; Regensburger Geographische Schriften: Regensburg, Germany, 2001; Volume 35, pp. 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, D.; Luansang, C.; Boonmahathanakorn, S. Facilitating community mapping and planning for citywide upgrading: The role of community architects. Environ. Urban. 2012, 24, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A. Orangi Pilot Project: The expansion of work beyond Orangi and the mapping of informal settlements and infrastructure. Environ. Urban. 2006, 18, 451–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, E. Mapping change: Community information empowerment in Kibera (innovations case narrative: Map Kibera). In Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 69–94. [Google Scholar]

- Samper, J. Physical Space and Its Role in The Production and Reproduction of Violence in the “Slum Wars” in Medellin, Colombia (1970s–2013); Massachusetts Institute of Technology MIT: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kamalipour, H. Improvising Places: The Fluidity of Space in Informal Settlements. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; AlSayyad, N. Urban Informality: Transnational Perspectives from the Middle East, Latin America, and South Asia; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA; Berkeley, CA, USA, 2004; ISBN 0-7391-0741-0. [Google Scholar]

- UN, D.I.U. Unstats|Millennium Indicators. Available online: http://mdgs.un.org/unsd/mdg/SeriesDetail.aspx?srid=710 (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- Angeles, G.; Lance, P.; Barden-O’Fallon, J.; Islam, N.; Mahbub, A.Q.M.; Nazem, N.I. The 2005 census and mapping of slums in Bangladesh: Design, select results and application. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2009, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niebergall, S.; Loew, A.; Mauser, W. Integrative assessment of informal settlements using VHR remote sensing data—The Delhi case study. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2008, 1, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüther, H.; Martine, H.M.; Mtalo, E.G. Application of snakes and dynamic programming optimisation technique in modeling of buildings in informal settlement areas. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2002, 56, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stow, D.; Lopez, A.; Lippitt, C.; Hinton, S.; Weeks, J. Object-based classification of residential land use within Accra, Ghana based on QuickBird satellite data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2007, 28, 5167–5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuffer, M.; Barrosb, J. Urban morphology of unplanned settlements: The use of spatial metrics in VHR remotely sensed images. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2011, 7, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayunga, S.D.; Coleman, D.J.; Zhang, Y. A semi-automated approach for extracting buildings from QuickBird imagery applied to informal settlement mapping. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2007, 28, 2343–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Lu, X.X.; Sellers, J.M. A global comparative analysis of urban form: Applying spatial metrics and remote sensing. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 82, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taubenböck, H.; Kraff, N.J.; Wurm, M. The morphology of the Arrival City-A global categorization based on literature surveys and remotely sensed data. Appl. Geogr. 2018, 92, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, D.; Sliuzas, R.; Kerle, N.; Stein, A. An ontology of slums for image-based classification. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2012, 36, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baud, I.; Kuffer, M.; Pfeffer, K.; Sliuzas, R.; Karuppannan, S. Understanding heterogeneity in metropolitan India: The added value of remote sensing data for analyzing sub-standard residential areas. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2010, 12, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B.; Greene, M.; Desyllas, J. Correspondence Self-generated Neighbourhoods: The role of urban form in the consolidation of informal settlements. Urban Des. Int. 2000, 5, 61–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samper, J. Eroded resilience, Informal settlements predictable urban growth implications for self-governance in the context of urban violence in Medellin, Colombia. UPLanD-J. Urban Plan. Landsc. Environ. Des. 2017, 2, 183–206. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, V.; Rybczynski, W. How the other half builds. Time-Saver Standard Urban Design; McGraw-Hill New York: New York, NY, USA, 2003; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kamalipour, H. Mapping Urban Interfaces: A Typology of Public/Private Interfaces in Informal Settlements. Spaces Flows Int. J. Urban Extra Urban Stud. 2017, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalipour, H.; Dovey, K. Incremental urbanisms. In Mapping Urbanities; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 249–267. ISBN 1-138-23360-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, G. An ecological approach to the study of urban spaces: The case of a shantytown in Brasilia. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 1997, 14, 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis, C.; Psaltis, C.; Potsiou, C. Towards a strategy for control of suburban informal buildings through automatic change detection. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2009, 33, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurskainen, P.; Pellikka, P. Change detection of informal settlements using multi-temporal aerial photographs–the case of Voi, SE-Kenya. In Proceedings of the 5th African Association of Remote Sensing of the Environment Conference, Nairobi, Kenya, 18–21 October 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shafqat, R.; Marinova, D. Using Mixed Methods to Understand Spatio-Cultural Process in the Informal Settlements: Case Studies from Islamabad, Pakistan. Humans 2022, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caminos, H.; Turner, J.F.; Steffian, J.A. Urban Dwelling Environments: An Elementary Survey of Settlements for the Study of Design Determinants; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1969; ISBN 0-262-03028-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, P.M. The Squatter Settlement as Slum or Housing Solution: Evidence from Mexico City. Land Econ. 1976, 52, 330–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.F.C. Housing by People: Towards Autonomy in Building Environments; Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1977; ISBN 0-394-40902-7. [Google Scholar]

- Holston, J. Autoconstruction in Working-Class Brazil. Cult. Anthropol. 1991, 6, 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goethert, R.; Director, S. Incremental housing. Monday Dev. 2010, 9, 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Nohn, M.; Goethert, R. Growing Up! The Search for High-Density Multi-Story Incremental Housing; SIGUS-MIT & TU Darmstadt: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Samper, J.; Marko, T. (Re)Building the City of Medellín: Beyond State Rhetoric vs. Personal Experience—A Call for Consolidated Synergies. In Housing and Belonging in Latin America; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 105. [Google Scholar]

- Augustijn-Beckers, E.-W.; Flacke, J.; Retsios, B. Simulating informal settlement growth in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: An agent-based housing model. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2011, 35, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobreira, F.; Gomes, M. The Geometry of Slums: Boundaries, packing and diversity. CASA 2001, 30, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Beardsley, J.; Werthmann, C. Improving Informal Settlements: Ideas from Latin America. Harvard Design Magazine Spring 2008, Can Designers Improve Life in Non-Formal Cities? 28, 31–34. Available online: https://www.harvarddesignmagazine.org/issues/28/improving-informal-settlements-ideas-from-latin-america (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- Sietchiping, R. Predicting and Preventing Slum Growth: Theory, Method, Implementation and Evaluation; VDM-Verlag Müller: Riga, Latvia, 2008; ISBN 3-639-03626-3. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, A. Slumulation: An integrated Simulation Framework to Explore Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of Slum Formation in Ahmedabad, India; George Mason University: Fairfax, VA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond, D. Architectes des Favelas; Pratiques de l’espace; Dunod: Paris, France, 1981; Volume 1, ISBN 2-04-012091-2. [Google Scholar]

- Mesa Sánchez, N.E. Proceso de Desarrollo de Los Asentamientos Populares No Controlados: Estudios de Caso Medellín; Repositorio Institucional UN, National University of Colombia: Bogota, Colombia, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, S.M. “Young Town” Growing Up: Four Decades Later: Self-Help Housing and Upgrading Lessons from a Squatter Neighborhood in Lima; Massachusetts Institute of Technology MIT: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Owusu, M.; Kuffer, M.; Belgiu, M.; Grippa, T.; Lennert, M.; Georganos, S.; Vanhuysse, S. Towards user-driven earth observation-based slum mapping. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2021, 89, 101681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samper, J. Atlas of Informality. Available online: www.atlasofinformality.com (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- Adams, C. Spatial Resolution of Google Earth Imagery. Available online: https://gis.stackexchange.com/ (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- Qi, F.; Zhai, J.Z.; Dang, G. Building height estimation using Google Earth. Energy Build. 2016, 118, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohl, C.C.; Plater-Zyberk, E. The Transect—Building Community across the Rural-to-Urban Transect. Places 2005, 18, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Duany, A. Introduction to the special issue: The transect. J. Urban Des. 2002, 7, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, P.; Taubenböck, H.; Werthmann, C. Monitoring and Modelling of Informal Settlements-A Review on Recent Developments and Challenges. In Proceedings of the 2015 Joint Urban Remote Sensing Event (JURSE), Lausanne, Switzerland, 30 March–1 April 2015; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Buhl, J.; Gautrais, J.; Reeves, N.; Solé, R.V.; Valverde, S.; Kuntz, P.; Theraulaz, G. Topological patterns in street networks of self-organized urban settlements. Eur. Phys. J. B-Condens. Matter Complex Syst. 2006, 49, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheuya, S. Reconceptualizing housing finance in informal settlements: The case of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Environ. Urban. 2007, 19, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovey, K. Informalising architecture: The challenge of informal settlements. Archit. Des. 2013, 83, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamete, A.Y. Missing the point? Urban planning and the normalisation of ‘pathological’spaces in southern Africa. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2013, 38, 639–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, I. Introduction: Re-spatialising urban informality: Reconsidering the spatial politics of street work in the global South. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2019, 41, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hare, G.; Abbott, D.; Barke, M. A review of slum housing policies in Mumbai. Cities 1998, 15, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabindoo, P. Rhetoric of the ‘slum’ Rethinking urban poverty. City 2011, 15, 636–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huchzermeyer, M. Troubling continuities: Use and utility of the term ‘slum.’. In The Routledge Handbook on Cities of the Global South; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2014; pp. 108–119. ISBN 0-203-38783-X. [Google Scholar]

- Samper, J. Overcrowding innovation: How informal settlements develop sustainable urban practices. In Retroactive; sixth edition of Lisbon Architecture Triennale; Circo de Ideias: Porto, Portugal, 2022; p. 120. ISBN 978-989-33-3797-4. [Google Scholar]

- Samper, J. INformality Process Strategies. In Does Effective Planning Really Exist? Syntagma: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 69–86. ISBN 978-3-940548-60-3. [Google Scholar]

- Wurm, M.; Taubenböck, H. Detecting social groups from space–Assessment of remote sensing-based mapped morphological slums using income data. Remote Sens. Lett. 2018, 9, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Comments

Post a Comment